Developing and Upstreaming a Linux hwmon Power Monitor Driver

February 02, 2026

Intro

Here I’ll share my perspective on upstreaming a modern hwmon driver into Linux kernel, with a bit of backstory.

I’m working on a network-connected battery charge/discharge monitor, focused on remote control, telemetry and automation. Bidirectional current measurement is needed to track charge and discharge cycles and compute net energy flow, with data exposed over the network as well as on-board web presentation. The system runs on Linux for robust networking, standard interfaces, and combining hardware measurement with software-defined behavior. For power monitor chip I chose the ST TSC1641 for its precision, wide voltage range, integrated power measurement and bidirectional current sensing.

As the prototype took shape, writing a Linux driver became a necessity. Also, around that time I applied and was going through the Linux Kernel Mentorship Program to gain guidance on upstream workflows and best practices. Huge thanks to Shuah Khan, David Hunter and other mentors for providing useful feedback on patch formatting, review etiquette and kernel conventions, which helped me approach contributions more confidently.

Once the driver basic functionality was in place, upstreaming it became the logical next step. That meant integration with libsensors via standard sysfs, long-term maintenance and benefit from kernel review (turns out “works on my board” is not quite a kernel standard). I wanted it to be more robust, reusable, and hopefully useful to others as well.

TSC1641 Hardware Overview

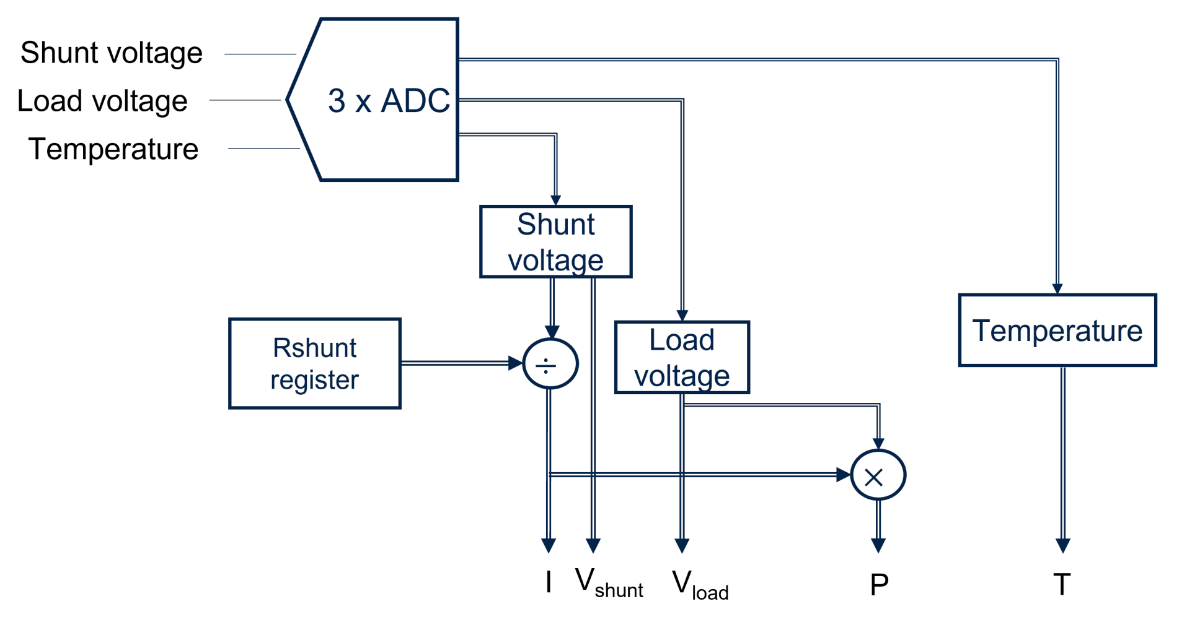

The TSC1641 is a high-precision 16-bit power monitoring IC that measures bus voltage, shunt voltage (and hence derived current) and temperature. Cool thing about it is that it has built-in real-time power calculation derived from input and shunt voltage, which simplifies design a little bit, as well as bidirectional current measurement support which is crucial for battery charge/discharge monitoring.

Here’s the basic structure of the measurement path:

Figure 1. TSC1641 voltage, current, power and temperature measurements (from datasheet)

Figure 1. TSC1641 voltage, current, power and temperature measurements (from datasheet)

The device supports I2C interface, which is important because multiple devices would need to be connected simultaneously to support multi-channel operation. TSC1641 supports MIPI I3C as well, which is I2C's cooler cousin, with higher bandwidth and nice bus arbitration. But for this design I3C won't solve any real problem, as bandwidth is sufficient and topology is simple. It also has pretty limited SoC support still, but eventually I would want to add I3C support.

The TSC1641 allows the assertion of several alerts regarding the voltage, current, power and temperature. Thresholds can be set for each parameter in a specific register.

As we’ll see later these thresholds and alerts will need to be mapped to the relevant sysfs attributes in the driver code. Another thing the Linux driver will need to account for is ALERT/DRDY pin - multi-functional digital alert pin that can be used as SMBus alert among other things.

To avoid reciting the entire datasheet here, here’s the link: TSC1641 datasheet

The hwmon Subsystem

The first choice when writing a kernel driver is in which subsystem it should land. Luckily for me it was a straightforward choice. The Linux hwmon subsystem standardizes access to system‑health sensors that measure voltage, current and temperature: board controllers, PMICs, fan controllers etc. and also related events and alerts. The goals is to let tools like lm-sensors read them consistently via sysfs.

In the simplest terms your hwmon device will be mapped into a directory in the filesystem at /sys/class/hwmon/hwmon*. The hwmon driver will expose a range of attributes (defined by the nature of the chip) which are simply mapped into files.

Most typical attributes will be:

update_interval how often to update value

in[0-*] voltage, millivolt

fan[1-*] fan control, RPM

pwm[1-*] fan PWM control, 0-255

temp[1-*] temperature, millidegree C

curr[1-*] current, milliamp

power[1-*] power, microwatt

energy[1-*] energy, microjoule

humidity[1-*] humidity, millipercent

For more information on hwmon sysfs conventions see hwmon sysfs ABI

TSC1641 matches this model perfectly - it continuously measures voltage, current, temperature, and power; exposes thresholds and faults; and supports SMBus Alert for asynchronous notifications. Its registers map cleanly to hwmon classes above (in, curr, temp, power), so the hwmon is the perfect home for its Linux driver.

One note about thresholds and alerts in hwmon that I stumbled on. The hwmon subsystem provides several attributes that can be possibly used as means of indicating alarm:

lcrit critical low value

min minimum value

max maximum value

crit critical high value

temp[1-*]_emergency only for chips supporting more than two upper temperature limits

In the first iteration I used crit attribute for alerts, but this is not quite what ABI implies. If you have a single alert level per value

(as in TSC1641) the idea is that you should use min or max first, before resorting to lcrit and crit. This was rectified during the review.

We talked about the standard hwmon attributes. If non-standard attributes are required by the driver it can implement them,

but it's advised to implement only the minimum subset. In our case shunt_resistor attribute is warranted,

to allow run-time configuration of shunt resistor value.

Taking into account the above information and compiling available features and registers from the datasheet, we can arrive to the final mapping of TSC1641 capabilities to hwmon attributes:

in0_input bus voltage (mV)

in0_max bus voltage max alarm limit (mV)

in0_max_alarm bus voltage max alarm limit exceeded

in0_min bus voltage min alarm limit (mV)

in0_min_alarm bus voltage min alarm limit exceeded

curr1_input current measurement (mA)

curr1_max current max alarm limit (mA)

curr1_max_alarm current max alarm limit exceeded

curr1_min current min alarm limit (mA)

curr1_min_alarm current min alarm limit exceeded

power1_input power measurement (uW)

power1_max power max alarm limit (uW)

power1_max_alarm power max alarm limit exceeded

shunt_resistor shunt resistor value (uOhms)

temp1_input temperature measurement (mdegC)

temp1_max temperature max alarm limit (mdegC)

temp1_max_alarm temperature max alarm limit exceeded

update_interval data conversion time (1 - 33ms), longer conversion time

corresponds to higher effective resolution in bits

Now having a clear mental picture of attributes we need to support in the driver, lets move to design decisions driven by subsystem conventions.

Driver Architecture

Integer arithmetic

One fact about Linux kernel is that it doesn't support floating point. In fact it doesn't touch FPU at all. Saving/restoring FPU states on every context switch would add huge overhead and some systems don't have FPU to begin with, so the portability is another reason why. This has important implications to hwmon as it deals with the

real world values and hence - real numbers. All of those numbers should be stored as integers and converted accordingly.

This is why DIV_ROUND_CLOSEST and similar macros can be found everywhere:

regval = DIV_ROUND_CLOSEST(val, TSC1641_VLOAD_LSB_MVOLT);

and hwmon generally deals in milli-, micro- and occasionally nano- suffixes

#define TSC1641_VSHUNT_LSB_NVOLT 2500 /* Use nanovolts to make it integer */

How to connect to sysfs

Now let's look at how the sysfs attributes gets mapped into driver code.

Actual starting point is inside the probe():

hwmon_dev = devm_hwmon_device_register_with_info(dev, client->name,

data, &tsc1641_chip_info, tsc1641_groups);

Here we basically registering our hwmon device. You can see that hwmon_chip_info is

being used as a parameter. Let's look at it and couple other related data structures:

static const struct hwmon_chip_info tsc1641_chip_info = {

.ops = &tsc1641_hwmon_ops,

.info = tsc1641_info,

};

static const struct hwmon_channel_info * const tsc1641_info[] = {

HWMON_CHANNEL_INFO(chip,

HWMON_C_UPDATE_INTERVAL),

HWMON_CHANNEL_INFO(in,

HWMON_I_INPUT | HWMON_I_MAX | HWMON_I_MAX_ALARM |

HWMON_I_MIN | HWMON_I_MIN_ALARM),

HWMON_CHANNEL_INFO(curr,

HWMON_C_INPUT | HWMON_C_MAX | HWMON_C_MAX_ALARM |

HWMON_C_MIN | HWMON_C_MIN_ALARM),

HWMON_CHANNEL_INFO(power,

HWMON_P_INPUT | HWMON_P_MAX | HWMON_P_MAX_ALARM),

HWMON_CHANNEL_INFO(temp,

HWMON_T_INPUT | HWMON_T_MAX | HWMON_T_MAX_ALARM),

NULL

};

static const struct hwmon_ops tsc1641_hwmon_ops = {

.is_visible = tsc1641_is_visible,

.read = tsc1641_read,

.write = tsc1641_write,

};

Most interesting of them is hwmon_channel_info which defines the attributes for

each channel: chip (for update interval), voltage, current, power and temperature.

Now if we look at the tsc1641_is_visible function snippet, we'll see how each attribute visibility is defined

with standard Unix permission bits:

static umode_t tsc1641_is_visible(const void *data, enum hwmon_sensor_types type,

u32 attr, int channel)

{

switch (type) {

...

case hwmon_in:

switch (attr) {

case hwmon_in_input:

return 0444;

case hwmon_in_min:

case hwmon_in_max:

return 0644;

case hwmon_in_min_alarm:

case hwmon_in_max_alarm:

return 0444;

default:

break;

}

break;

...

}

Here the input voltage and voltage alarms are read-only and voltage alarm threshold is read/write.

Using regmap

If we trace the call from sysfs read through hwmon_ops.read to the logical end,

we'll find the code that reads from the actual registers. Here's input voltage reading for example:

static int tsc1641_in_read(struct device *dev, u32 attr, long *val)

{

...

reg = TSC1641_LOAD_VOLTAGE;

...

ret = regmap_read(regmap, reg, ®val);

if (ret)

return ret;

...

}

This brings us to a very important attribute of a "modern" hwmon driver - use of regmap.

regmap is the kernel generic register access mechanism used by drivers.

Using regmap keeps your attention focused on hardware behavior instead of bus mechanics, which makes the code easier to read and reason about.

It also gives you a lot of stuff out of the box - standardized locking, caching and tracing.

Inside the TSC1641 driver, regmap is initialized inside the probe():

data->regmap = devm_regmap_init_i2c(client, &tsc1641_regmap_config);

With configuration looking something like that:

static const struct regmap_config tsc1641_regmap_config = {

.reg_bits = 8,

.val_bits = 16,

.use_single_write = true,

.use_single_read = true,

.max_register = TSC1641_MAX_REG,

.cache_type = REGCACHE_MAPLE,

.volatile_reg = tsc1641_volatile_reg,

.writeable_reg = tsc1641_writeable_reg,

};

Using devm

From snippets above one can see that a lot of initialization calls are prepended with devm_.

devm is the Linux kernel’s device-managed resource framework.

It ties allocated resources to the lifetime of a specific struct device so they are automatically released when the device is unbound, probe fails or the driver is removed.

Using devm when possible is the recommended approach. Using devm_* APIs makes the driver lifecycle match the device lifecycle, so probe and removal behave correctly without cleanup code. It keeps the driver resilient to probe failures or deferrals.

For example:

struct tsc1641_data *data;

data = devm_kzalloc(dev, sizeof(*data), GFP_KERNEL);

When using devm_kzalloc in probe(), if probe() fails halfway through, or if the device is later removed, the memory is freed automatically.

No unwind logic, with less potential for leaks, double-frees, etc.

What had to be improved during review

My first version of the patch didn't pay enough attention to all the failure modes that chip can report.

I had to make sure that every possible failure case is taken care of in the driver and relevant error code is returned.

Oftentimes -ENODATA is a logical choice.

For instance, when dealing with shunt voltage register, datasheet spells out this failure scenario:

This read-only register stores the value measured on the shunt resistor. Positive value is binary: positive full-scale goes from 0000(h) to 7FFF (hex). Negative value is two’s complement. Negative full-scale goes from 8000(h) (two’s complement of decimal -32767 to 000(h)). If the register returns either 7FFF or 8000, together with the bit SATF set to ‘1’, the shunt voltage is out of the input range of the TSC1641.

Which translates to the following code:

/* Check if load voltage is out of range */

if (reg == TSC1641_LOAD_VOLTAGE) {

/* Register is 15-bit max */

if (regval & 0x8000)

return -ENODATA;

ret = tsc1641_flag_read(regmap, TSC1641_SAT_FLAG, &sat_flag);

if (ret)

return ret;

/* Out of range conditions per datasheet */

if (sat_flag && (regval == 0x7FFF || !regval))

return -ENODATA;

}

Another aspect of hwmon driver that came up often during review process is clamping the values.

Care should be taken that no possible combination of inputs leads to numeric overflow. Here when writing current we

clamp twice, first to prevent val * 1000 from overflowing and then clamp to the maximum range of a signed 16-bit register:

/* Clamp to prevent over/underflow below */

val = clamp_val(val, -TSC1641_CURR_ABS_MAX_MAMP, TSC1641_CURR_ABS_MAX_MAMP);

/* Convert val in milliamps to register */

regval = DIV_ROUND_CLOSEST(val * 1000, data->current_lsb_ua);

/*

* Prevent signed 16-bit overflow.

* Integer arithmetic and shunt scaling can quantize values near 0x7FFF/0x8000,

* so reading and writing back may not preserve the exact original register value.

*/

regval = clamp_val(regval, SHRT_MIN, SHRT_MAX);

Testing

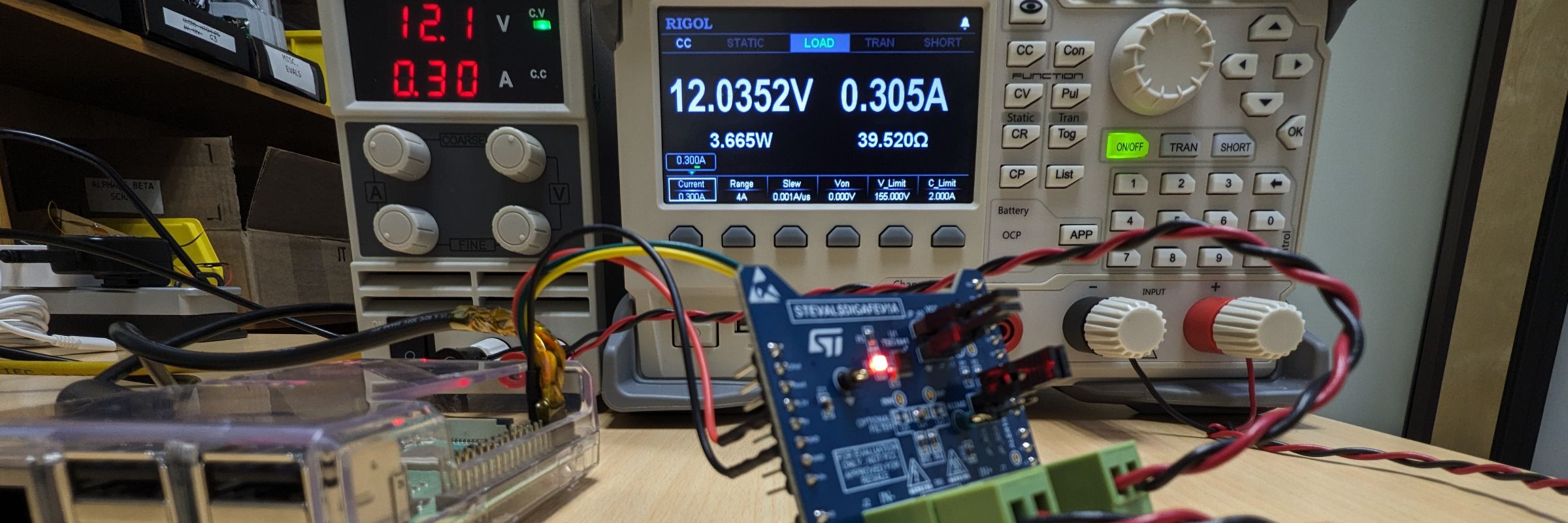

Since I'm still finalizing the hardware part of the design, I needed some platform to test my driver early. Since it's probably the easiest embedded target to get mainline kernel running on, I used Raspberry Pi 3B+. It gave me a stable hardware to which I can hook up I2C device for fast iteration without waiting for board bring-up.

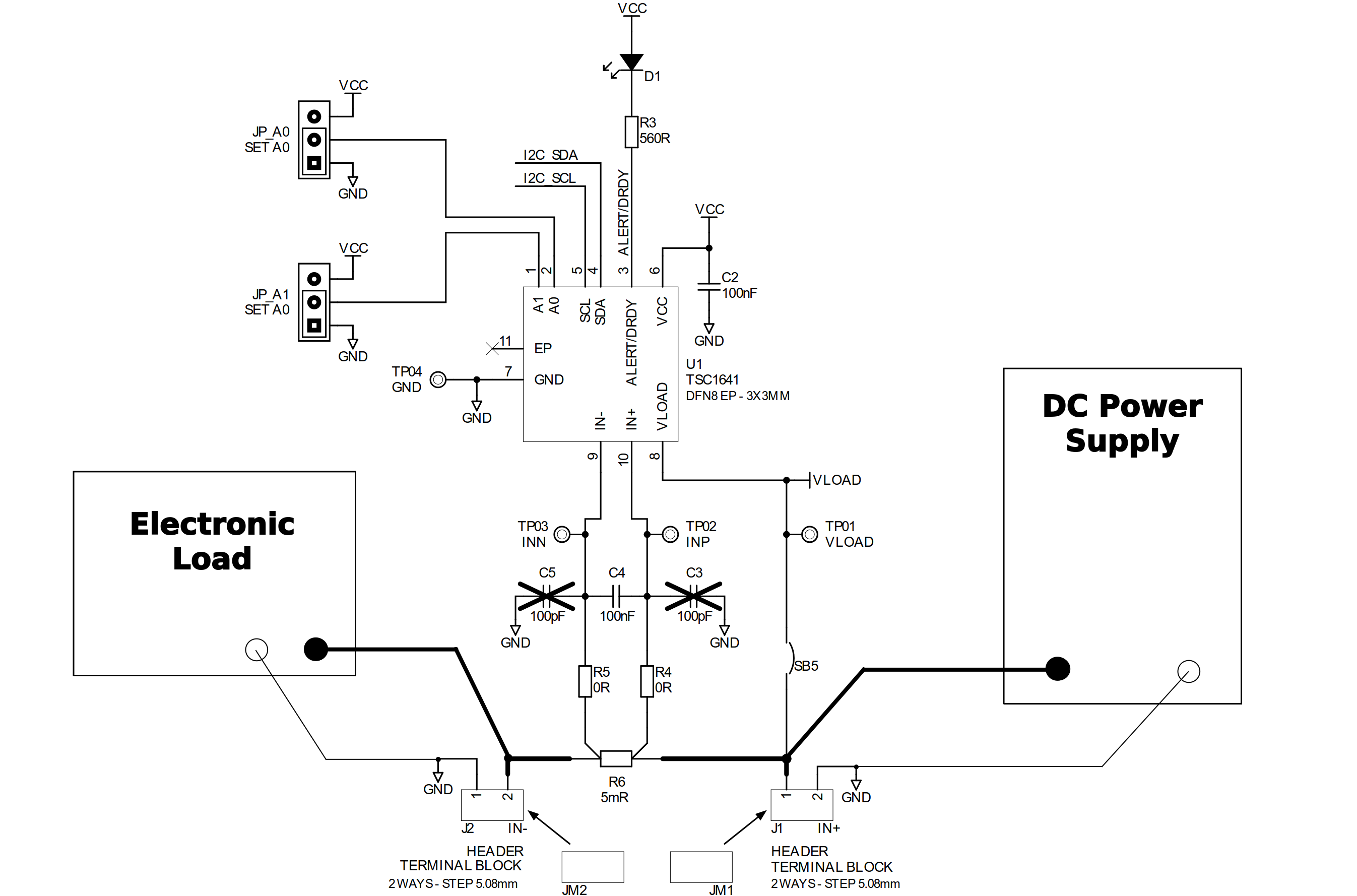

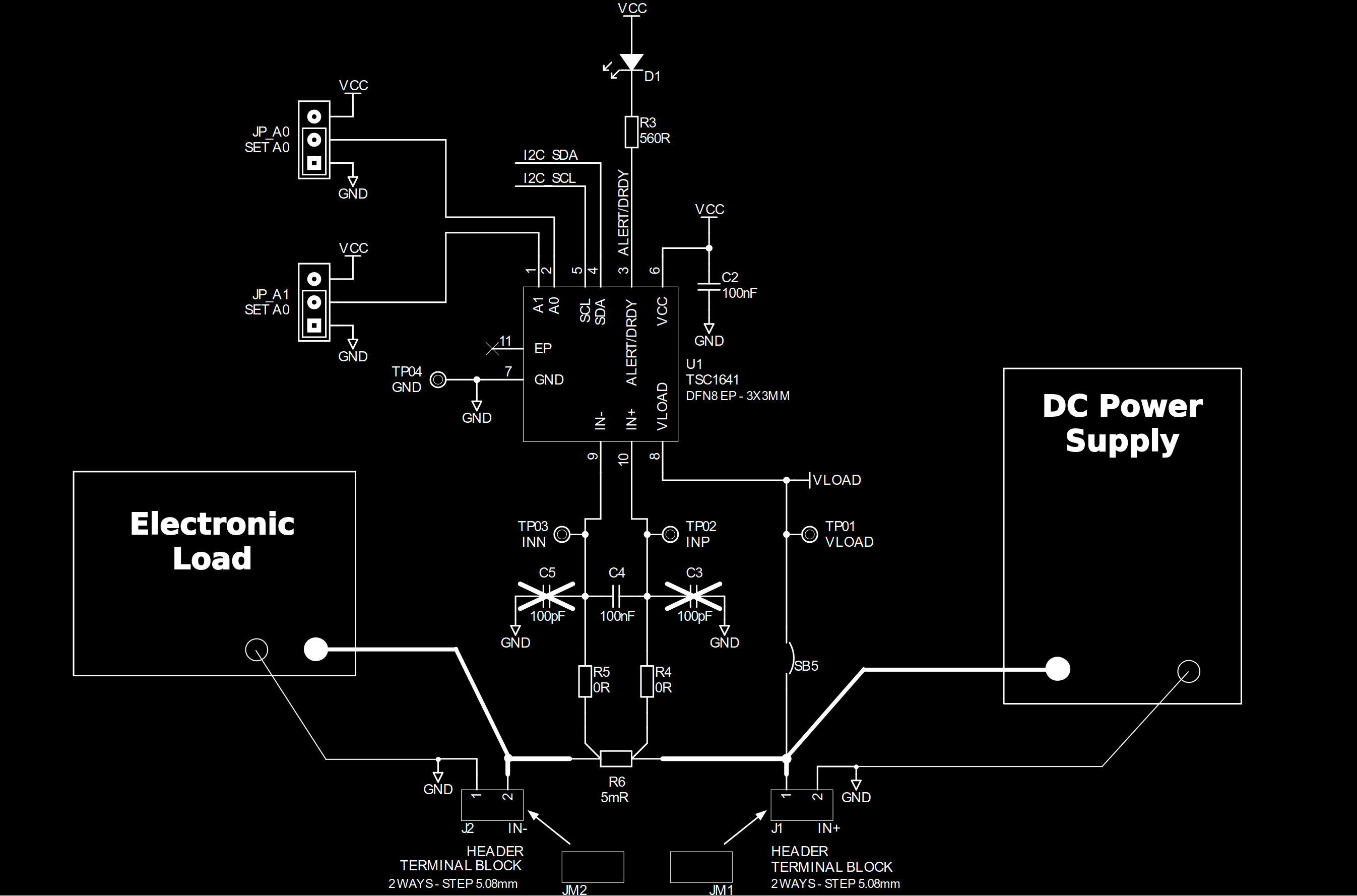

To validate the driver during development, I set up a simple bench using DC power supply, an electronic load and the STEVAL-DIGAFEV1 evaluation board hosting the TSC1641.

This allowed me to validate voltage, current and power measurements, as well as alert functionality. I used shell script that would poll the sysfs and verify that correct values and alerts are asserted during testing. Here's the illustration of the test setup:

Figure 2. TSC1641 test setup schematic (10000 hours in MS Paint)

I found R4 and R5 resistors placement especially convenient. After quick rework I added a jumper block using those connection points.

With this I was able to switch perceived current direction easily, which allowed to emulate 2 quadrant power cycle.

Device Tree

No discussion of the kernel driver can be complete without discussing it's Device Tree binding.

In the current Linux your driver simply won't be accepted without complete (as much as possible) and valid binding.

Historically bindinds were just plaintext files. They explained how device should be described, but didn't enforce anything.

Now the mechanism in use is DT schema. A DT schema is YAML formatted json-schema file that describes how

your device is presented in Device Tree source file. Nice thing is that it can be automatically verified and indeed when you run make dtbs all the .dts files get

checked against their schemas.

One of the important reasons why bindings are required prior to new driver addition is that Device Tree is a stable ABI. Once a binding is merged, it must be supported indefinitely. A poorly written binding creates mistakes that cannot be fixed without breaking existing systems. Requiring a schema upfront forces the driver author to think about long-term compatibility and clarity before code is accepted.

In practice, the schema review is often as strict or stricter than the driver review. This ensures that hardware description is precise and unambigious. Only once that contract exists does it make sense to merge a driver that depends on it.

I will forgo discussing bindings in detail in this article as it's a big topic in of itself. More can be found inside the kernel documentation.

Here, I will give a link to st,tsc1641.yaml schema in the kernel tree and go over relevant properties:

compatible: - is what device string your schema is compatible with.

reg: - in our case means the I2C address of our device on the bus.

interrupts: - is optional as TSC1641 ALERT/DRDY pin may or may not be used as interrupt.

shunt-resistor-micro-ohms: - is not only a sysfs attribute but also a devicetree property. We'll

find it later in the actual .dts description.

st,alert-polarity-active-high: - alert pin polarity can be optionally inverted to be active high. This property does just that.

Since I used a Raspberry Pi 3B+ as a stand-in to develop and validate the driver I needed to define my device inside its Device Tree.

Now, it's possible to patch Pi 3B+ /dts in-tree to enable st,tsc1641, but it's not the best approach. Much cleaner and more standard way

to do this is to use Device Tree overlay.

An overlay is a mechanism for modifying or extending an existing Device Tree at runtime, without rebuilding or replacing the base Device Tree blob.

You apply it on top of the existing devicetree, hence the overlay. It can add new nodes, enable or disable devices or change properties.

Here's how the overlay looks like for our device:

/dts-v1/;

/plugin/;

/ {

compatible = "brcm,bcm2837";

fragment@0 {

target = <&i2c1>;

__overlay__ {

#address-cells = <1>;

#size-cells = <0>;

tsc1641@40 {

compatible = "st,tsc1641";

reg = <0x40>;

shunt-resistor-micro-ohms = <5000>;

};

};

};

};

You can see the reg being set to 0x40 since it's a default I2C address of the chip.

Note the compatible = "brcm,bcm2837" line. Since I was testing on Raspberry Pi 3B+ this is the SoC model

and the name of original .dts the overlay is running on top of.

Upstreaming Process

There’s a bunch of information available on mechanics of upstreaming process, so I'm not going to dive too deep into it. Good place to start is probably kernel documentation

I will try to highlight some aspects of it and the approach that I took.

First of all - the mailing list. I used git send-email to interract with LKML.

I know people had success with setting up other email clients, but I foud it too cumbersome.

I know stuff like Gmail simply won’t work for patches, maybe it can be setup for general discussion.

I didn't used b4 as I don't have a ton of complex patches, so I find simple workflow sufficient.

Let’s look at the patch series structure for the driver, as there’s some important details there. First of all, a patch should be self-contained and apply cleanly in isolation. Another thing - the order of patches in the patchset is important. If you add a Device Tree schema for the device driver, the schema patch should come first.

That's how patch series structure looked like:

[PATCH 0/2] Cover letter

[PATCH 1/2] dt-bindings: hwmon: ST TSC1641 power monitor

Documentation/devicetree/bindings/hwmon/st,tsc1641.yaml | 63 +++++++++++++++++++

[PATCH 2/2] hwmon: Add TSC1641 I2C power monitor driver

Documentation/hwmon/index.rst | 1 +

Documentation/hwmon/tsc1641.rst | 87 ++++

drivers/hwmon/Kconfig | 12 +

drivers/hwmon/Makefile | 1 +

drivers/hwmon/tsc1641.c | 748 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

note how Kconfig, Makefile and documentation are bundled together. Applying them separately would not only make little sense, but could break the build.

Overall the development loop looked something like that:

- Build against multiple architectures, if possible. Since I was cross-compiling for arm64 I could test 2 builds - x86 and arm64.

- Test (see above)

git commitandgit rebaseas needed- Run static analysis:

make C=1 ... KCFLAGS="-Wall -Wextra -Wunused" - Instal dtschema and run check on your binding:

make DT_SCHEMA_FILES={your.yaml} dt_binding_check - Run checkpatch to detect style and formatting issues:

scripts/checkpatch.pl --strict {your.patch} - Run

scripts/get_maintainer.pl {your.patch}to get maintainers and mailing list addresses - Submit with

git send-email --to={emails} {your.patch} - Get reviews, fix and repeat

Beyond that, there’s pretty extensive checklist on kernel docs

After submitting, my patchset went through 4 iterations before being merged.

To summarize what had to change to meet upstream standards:

-- Really nail the binding definition

-- It took couple iterations before I figured out how to map my driver to sysfs ABI

-- Robust clamping and input validation

Conclusion

Writing the TSC1641 hwmon driver started as a way to get a networked battery monitor working, but taking it upstream turned the work into something that could actually live beyond my own board. Following hwmon subsystem conventions, sysfs ABI expectations and kernel review pushed me to prioritize clarity and correctness over quick fixes. It was a reminder that in the kernel, getting the hardware to function is rarely the hardest part - the hard part is making a solution that others can understand, use, and maintain for years to come.

With the TSC1641 driver

now in the mainline Linux, it becomes a small but stable building block. I'm glad that the work I started can genuinely help other developers and projects.

Big thanks to the subsystem maintainers and reviewers for their deep feedback that pushed my patches to be cleaner, simpler and better.